INTRODUCTION

Protein S is a vitamin K-dependent anticoagulant protein. Which prevents clotting by acting as a cofactor for activated protein C in the degradation of clotting factors Va and VIIa. An inherited or acquired deficiency of protein S leads to a prothrombotic state, with predisposition to thrombosis. Its deficiency is a rare condition and can lead to deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or stroke.

Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) is a relatively rare cause of stroke, and it has been reported to cause 0.5ŌĆō1.0 % of all strokes1-2). Isolated cortical vein thrombosis (ICVT) is the thrombosis of 1 or more cerebral cortical veins without occlusion of the major dural venous sinuses or the deep cerebral veins. ICVT accounts for less than 1% of all cerebral infarctions and has only been reported in case reports and small patient series. Here, we report an extremely rare case of an ICVT patient with type II Protein S deficiency

CASE REPORT

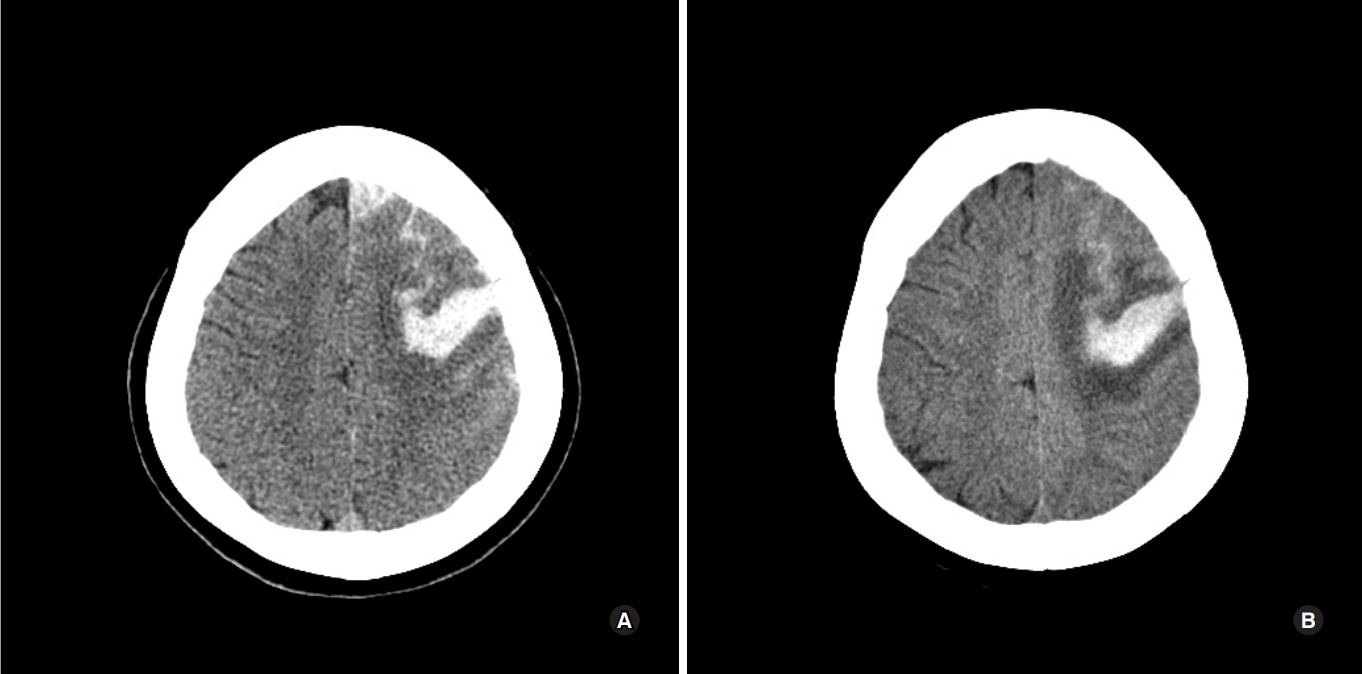

A 59-year-old woman, who was admitted to the emergency department due to right-sided hemiparesis and aphasia. She was alert, and had apparent right side motor weakness, when she woke up at 9 AM. She had no medical history and family history of cerebral infarction of hers mother. On admission, body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure were 37 ┬░C, 88 beats/min, and 130/80 mmHg, respectively. An initial computed tomography (CT) scan revealed acute intracerebral hemorrhage & subarachnoid hemorrhage in left frontal lobe and cortical sulcus (Fig. 1A). Considering the patientŌĆÖs age and absence of a hypertension history, brain CT angiography was performed to rule out conditions such as a cerebral aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation (AVM), or sinus thrombosis, and no such conditions were noted. Brain CT angiography showed diffuse narrowing of Lt ICA and severe stenosis (about 75%) at left supraclinoid ICA.

Her ICH was treated with conservative medical therapy in order to maintain systolic BP below 130 mmHg, including immediate intravenous administration of mannitol. MRI and cerebral angiography were planned on another day to identify the definite etiology

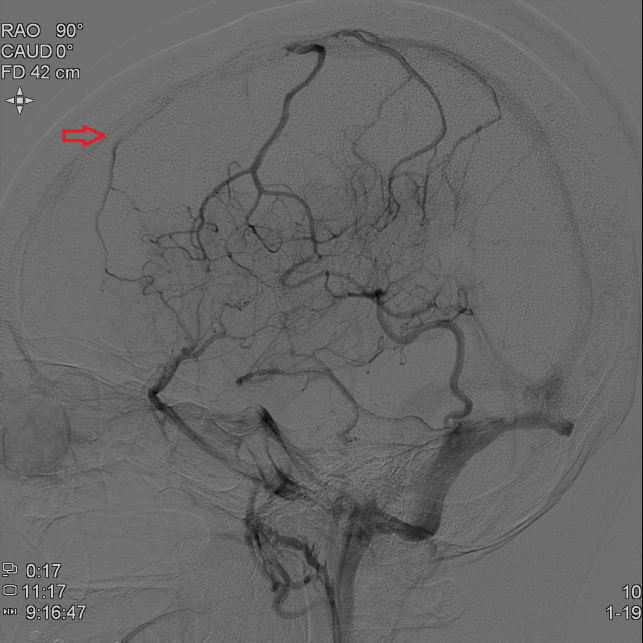

Magnetic resonance (MR) images and DSA confirmed a left frontal ICVT as the underlying disease. (Fig. 2)

At admission, the coagulation profile was assessed, and blood laboratory studies were performed to check for connective tissue diseases. No abnormal data was found, except that the protein S activity was low at 31 %. In hospital day 7th, she had a GTC type seizure. After postictal period, follow up brain CT showed no specific change (Fig. 1B). However, her condition rapidly deteriorated and she went into a coma approximately 2 hours after seizure. Her consciousness level was E1V1M2 on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). At chest CT, multifocal pulmonary thromboembolisms (PTE) in both lungs, acute to chronic phase, combined pulmonary hypertension and RV enlargement (Fig. 3). The patient had no significant dyspnea or chest discomfort symptom during admission. To address IVCT and PTE, systemic heparinization was promptly applied. Although the resolution of pulmonary embolism was confirmed after anticoagulation, she expired at hospital day 30th.

DISCUSSION

ICVT is rare in developed countries, with an incidence rate ranging from 1:10,000 to 1:25,000.11). There are no specific symptoms for ICVT. Diagnosis is very difficult owing to the conditionŌĆÖs rarity and the obscurity of symptoms. Of help, is to note a patientŌĆÖs background and history. Risk factors easily identifiable from a medical history included, pregnancy, puerperium, connective tissue disease, malignancy, contraceptive use, and infections such as, sinusitis, otitis, and mastoiditis4). Young individuals, especially young women, are more vulnerable. The International Study on ICVT reported that 78% of all cases were aged less than 50 years, and that the incidence of ICVT was three times greater in women than men4). When a young, pregnant, or postpartum woman presents with new onset, stroke-like symptoms, such as headaches and seizure, it is significant to examine for the ICVT risk factors. If ICVT is suspected, CT venography or MR venography should be performed. However, due to its small size, ICVT is hard to detect using these conventional modalities. A recent study proved that T2*/susceptibility-weighted MR imaging sequences are very effective in detecting such lesions. Treatment for ICVT is still controversial; however, heparin has been reported as a safe and effective treatment. This is true even when ICVT is accompanied by hemorrhagic lesions. Anti-seizure medication should be given to those who present with early seizures. Anticoagulation therapy for ICVT averts aggravation of the thrombus, and allows for improvement of the occlusion lesion. This therapy is supported by European Federation of Neurological Societies guidelines. However, in cases of hemorrhagic presentation, appropriate therapy is highly controversial. It has been reported that 39ŌĆō41% of ICVT patients present with ICH, hemorrhagic venous infarcts, or isolated subarachnoid hemorrhage5). Although heparin and warfarin have been used for more than 50 years, newer oral anticoagulants (eg. dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) might offer an alternative to traditional therapies for ICVT, and pulmonary thromboembolism6).

Protein S (named in reference to its isolation and characterisation in Seattle in 1979) is a vitamin K-dependent protein synthesised in the liver, vascular endothelium and megakaryocytes. It helps in cleaving activated clotting factors Va and VIIa on vascular endothelium by acting in association with protein C. PS deficiency is classified as type I (low total and free antigen, reduced activity), type II (normal total and free antigen, reduced activity), and type III (normal total antigen, reduced free antigen and activity). Our patient was diagnosed with type II PS deficiency, which is an extremely rare disease8). Few case reports have also implicated protein S deficiency in recurrent ischemic strokes in the young. Similarly, progressive intracranial occlusive disease has been reported in association with protein S deficiency. However, current data do not support an association between hereditary protein S deficiency and an increased risk of arterial thrombosis. The recommended therapy for ICVT is anticoagulation with heparin followed by oral anticoagulation, which should be continued indefinitely for patients with underlying thrombophilia.

CONCLUSION

Here, we presented an extremely rare case of an ICVT patient with type II PS deficiency. For early diagnosis, it is vital to suspect CVT, including ICVT, considering the patientŌĆÖs background. In such a case, CT-DSA should be performed and the images should be thoroughly checked. A hematoma associated with ICVT caused by a cortical vein might expand without early anticoagulation therapy, as was noted in our case. Therefore, early anticoagulation therapy might be essential, even in isolated cases involving ICH.