Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in a Patient with Spinal Metastasis

Article information

Abstract

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), also named reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy, is not a familiar term to neurosurgeon. The PRES is characterized by various kinds of neurologic signs and symptoms that include headache, seizure, altered mental status, lethalgy, visual loss and focal neurological disability. A 63-year-old female visited with upper back pain and both leg weakness. She has been receiving chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin for lung cancer with multiple bone metastasis. According to the imaging, we diagnosed the patient as T8 pathologic fracture. Five days after surgical decompression, she suddenly complained of visual loss. Magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) of the brain showed bilateral subcortical and cortical edema in the parieto-occipital area. Her MRI finding and symptoms suggested the PRES. Five days after conservative treatment, her visual disturbance was completely recovered. We believe that accurate and early detection of PRES and adequate treatment is very important for the patient having a history of chemotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

In 1996, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) was first described as reversible leukoencephalopathy by Hinchey1). This syndrome is characterized by various kinds of neurologic signs and symptoms that include headache, seizure, altered mental status, lethalgy, visual loss and focal neurologic defects2-4). PRES presents a variety of symptoms, so it is sometimes difficult to diagnose accurately. Classic neuroimaging of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) characteristically show bilateral cortical and subcortical edema, especially in the parieto-occipital areas. Although the pathogenesis of this syndrome remains controversial, hypertension, immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapeutic agents, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, electrolyte disturbance have been identified as risk factors2,3,5-7). PRES is not familiar with neurosurgeon, so early diagnosis and prompt treatment are very important because it can lead to permanent or severe neurological disability. And it is almost reversible and can be treated with conservative therapy. We report a case of PRES in patient with a history of chemotherapy.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old woman was admitted to a department of neurosurgery with a history of upper back pain and both leg weakness for 2 months. About two years ago, she was diagnosed with lung cancer and multiple bone metastasis. And she has been receiving chemotherapy for metastatic cancer in department of internal medicine. Six cycles of chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplantin had been completed 30 days prior to admission. Except metastatic lung cancer, she has not been diagnosed with other disease, including hypertension. MRI of thoracic spine revealed multiple fracture. And there were severe central canal stenosis and cord signal change in T8 spinal cord level due to collapse of 8th thoracic vertebral body (Fig. 1).

T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing the spinal metastatic tumors compressing spinal cord at the level of 8th thoracic vertebra.

We scheduled surgical decompression. T8 total laminectomy and T7, 9 subtotal laminectomy was performed and instrumentation on T6, 7, 9, 10, 11 was done. On the intraoperative field, a definite problem has not been found.

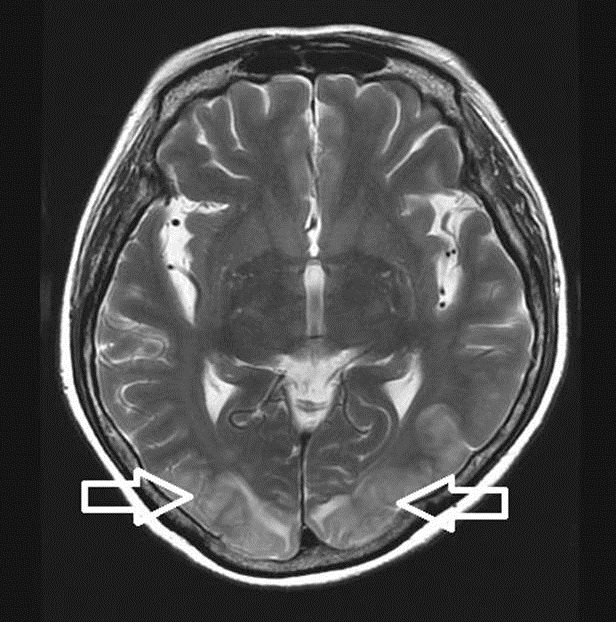

After the operation, back pain and motor grade have improved. Five days later, however, she suddenly complained of visual loss. The patient checked computed tomography(CT) scans initially, which didn’t show definite intracranial abnormality. After several minutes, a generalized tonic clonic seizure attack occurred. With sodium valproate 900mg loading, diazepam 10mg was given intravenously to control the seizure. After the seizure stopped, we transferred the patient to the intensive care unit and then she was scanned by MRI. T2-weighted imaging showed bilateral high intensity signal in the parieto-occipital regions(Fig. 2). According to the imaging, we diagnosed the patient as PRES. We checked her blood pressure during the operation and post operation, also. But her blood pressure was consistently within a normal range. Two days after being diagnosed as PRES, her vision gradually improved and there was no further seizure attack. And five days after the event, her visual disturbance was completely recovered.

DISCUSSION

We have reported a case of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). Hinchey et al. were first described as a reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome in 1996, and the name was changed to PRES in 2000 and since then the terminology has been widely used1,8). But PRES is not still familiar to most of neurosurgeons due to their limited experience.

PRES is generally associated with severe hypertension, eclampsia, preeclampsia, immunosuppressive treatment, electrolyte imbalance, chemotherapeutic agents and autoimmune disease. Especially, severe hypertension is regarded as the major risk factor in these patients. Some authors reported that about 70~80% of these patients have severe hypertension9,10). But similar to our case, PRES can occur even in the absence of severe hypertension. According to several studies, a few cases of PRES are associated with chemotherapeutic agent such as gemcitabine, cisplatin, 5-fluoruracil, oxaliplatin, cytarabine2,11).

Symptoms of PRES include headache, seizure, altered mentality, visual disturbance and focal neurological signs. According to the report of Roth et al.12) the one of the most common symptoms of the patient with PRES is seizure, which occurred in 84% of the patients. Visual disturbance was also found in 60% of these patients13). Most symptoms of PRES usually occur suddenly, so accurate and early diagnosis is important. Typically, PRES can be diagnosed by brain MRI. Cerebral edema involving the parieto-occipital area is seen as increased signal of T2 imaging and fluid attenuated inversion recovery(FLIAR) imaging13).

Although pathogenesis of PRES is still controversial, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that it is associated with vasogenic edema14). If the blood pressure is increases more than a certain level, the cerebral autoregulation can fails. Acute failure of cerebral autoregulation lead to disruption of the blood brain barrier and cerebral vasodilatation. Consequent leakage of transudation into the interstitium results in cerebral vasogenic edema.

Mechanism of chemotherapeutic agents related with PRES is also unclear. Cisplatin and gemcitabine are commonly used in many cancer patients, but it is not certain that which drug is main cause of PRES. Some authors have suggested that cisplatin induced PRES may be related to hypomagnesemia15), but that is not yet clear.

Eventually, control of leading cause is very important to this syndrome. If there was a history of high blood pressure, controlling of blood pressure is needed. If the patient is in the treatment of cancer chemotherapy, drug must be discontinued or changed to other drug. Typically, radiologic findings and clinical symptoms are reversible within 2 weeks after early and accurate treatment9,11). But if adequate treatment is not initiated or PRES is not diagnosed, irreversible ischemic damage may occur.

CONCLUSION

Although PRES is not familiar with surgeon, it is reversible with supportive therapy and control of leading cause. It is often difficult to diagnosis early and it can be progressively result in permanent neurologic damage. We believe that an accurate and prompt diagnosis of PRES is important to avoid permanent neurological disability for the patient having a history of chemotherapy.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.