Spontaneous Disappearance and Recanalization of Ruptured Pericallosal Artery Aneurysm

Article information

Abstract

We report a case of spontaneous disappearance and recanalization of ruptured pericallosal artery aneurysm. A patient in her 40s presented with semicomatose mentality and massive intraventricular hematoma. Initial computed tomography angiogram (CTA) showed definite saccular aneurysm on pericallosal artery. But, cerebral angiography while attempting urgent coil embolization showed disappearance of the ruptured aneurysm along with thrombotic occlusion of parent artery. Then, the patient had been receiving conservative management in the intensive care unit. The CTA was repeated on hospitalization day (HD) 7 and 14. Recanalization was detected on CTA of HD 22. The ruptured aneurysm was obliterated with endovascular coiling on the HD 23. The aneurysm has been stable for 36 months. Careful surveillance for recanalization followed by delayed intervention will be crucial in the exceptional situations of a spontaneously disappearing aneurysm.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous thrombosis seems to occur in natural course of unruptured large or giant aneurysm3). But it can occur even after a rupture of a relatively small aneurysm2,6,10). In the acute setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), it is a situation that required caution because spontaneous thrombosis is likely not a true cure10). And the timing of its recanalization is unpredictable, and subsequent fatal rebleeding is uncontrollable. Although ruptured aneurysm at any location can be spontaneously thrombosed, reports on spontaneous disappearance of ruptured distal anterior cerebral artery (DACA) aneurysm are scarce6,10). Here, we describe an exceptional case of spontaneous thrombosis and recanalization of ruptured pericallosal artery aneurysm.

CASE REPORT

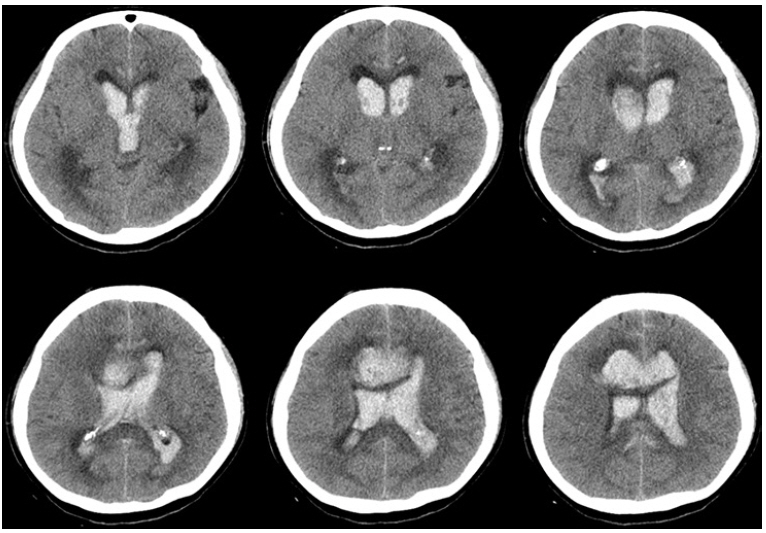

A female patient in her 40s, without underlying disease visited the emergency room with deteriorating consciousness. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed massive intraventricular hematoma with acute hydrocephalus and frontal intracerebral hematoma (Fig. 1). The patient presented semicomatose mentality with Glasgow coma scale (GCS) 1/1/2, World Federation of Neurosurgical Society grade V on the initial assessment. CT angiogram (CTA) revealed a saccular aneurysm in the pericallosal artery (Fig. 2). The patient's spontaneous breathing gradually became weaker and irregular. To avoid impending critical brain herniation, we decided to perform extraventricular drainage (EVD) before coil embolization. For concern of EVD induced rebleeding, Tranexamic acid was administrated intravenously and then EVD was performed. Then, patient was transferred to the angio suite. Left internal carotid artery (ICA) angiogram was performed but, aneurysm disappeared and the parent artery was not visualized distal to A2 segment due to thrombotic occlusion (Fig. 3). The procedure was stopped and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Tranexamic acid was no longer administered. CTA was repeated on the 7th, 14th, and 22nd hospitalization days (HD). Recanalization of the aneurysm was detected on the 22nd HD (Fig. 4A-C). Coil embolization was performed on the 23rd HD (Fig. 4D). Follow-up digital subtraction angiography (DSA) on the 27th postoperative day showed no interval change in the obliterated aneurysm. The patient was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital on the 51st HD with a state of GCS 4/T/6 and modified Rankin scale (mRS) score of 5. On the follow up 36 postoperative months, functional state of the patient was GCS 4/3/6 and mRS score 4. Follow-up DSA at 36 months postoperatively revealed no recurrence other than the small residue of the aneurysm neck.

Computed tomography (CT) scan showed massive intraventricular hematoma with acute hydrocephalus and intracerebral hematoma in corpus callosum.

(A) Initial Computed tomography (CT) angiogram revealed aneurysm located in the pericallosal artery without vasospastic feature of parent artery. (B) The aneurysm was located at the bifurcation site and measured 7.9 × 5.0 × 4.3 mm in size, with a narrow neck (2.8 mm).

Left internal carotid angiogram, anteroposterior view (A) and lateral view (B). The parent artery distal to A2 segment was not visualized on angiogram. White arrow indicates intraluminal filling defect suggestive of thrombotic occlusion.

(A) On hospitalization day (HD) 7, A2 and A3 were visualized on computed tomography (CT) angiogram. (B) The parent artery was more clearly delineated, and the aneurysm neck was slightly visible on HD 14. (C) Entire aneurysm was revealed on HD 22. (D) Coil embolization was performed on the next day of detecting recanalization.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have suggested possible mechanisms of spontaneous thrombosis. Turbulent flow and subsequent endothelial damage appear to be a major cause of spontaneous thrombosis in large or giant aneurysm3). It is speculated that use of the antifibrinolytics, vasospasm, and elongated aneurysm shape with thick hematoma around the aneurysm may be the mechanism of spontaneous disappearance of small ruptured aneurysms2,6,10). On DSA of our case, disappearance of the aneurysm is obviously due to thrombosis of the aneurysm and parent artery (Fig. 3). It clearly shows filling defects inside the lumen not the segmental narrowing as in vasospasm.

A blood blister-like aneurysm (BBA) can exhibit rapid morphological changes over time4,5). Rarely, BBA can occur in locations other than the ICA, and it may have a saccular shape5). However, the location of the denifite bifurcation site in our case does not match the typical BBA location of the nonbranching site4,5). Although spontaneous thrombosis may occur in the clinical course of ruptured dissecting aneurysm, the dissecting feature of proximal narrowing with pseudoaneurysm formation could not be found in angiograms in our case9).

Spetzler et al. described a possible relation between spontaneous thrombosis and the antifibrinolytics for preventing clot lysis induced rebleeding10). In a systematic review, it was reported that antifibrinolytic treatment reduced rebleeing rate of ruptured aneurysm up to 40%1). But it is not recommended as a routine practice because it does not improve mortality and clinical outcome1). Our situation was an exception, since we had no choice but to perform an EVD before aneurysm repair. Therefore Tranexamic acid (TXA) was inevitably used to reduce the possibility of rebleeding7). A recent multicenter study reported that even with no statistical significance, procedural thrombosis was more common in the group of SAH patients with TXA treatment8). Since we experienced this case, we have not used TXA in patients scheduled for urgent endovascular treatment.

Reports on spontaneous thrombosis of DACA aneurysms are scarce6,10). Yoshikazu et al. reported findings similar to our case. In their report, ruptured DACA aneurysm was seen in CTA at 2.5 hours after rupture, but DSA after 8.5 hours from rupture failed to reveal aneurysm6). They suggested an elongated shape with a narrow neck and thick hematoma compressing the aneurysm as a cause of spontaneous thrombosis6). The CT finding of a large intracerebral hematoma around the aneurysm in our case was similar to their report.

The recanalization timing after spontaneous thrombosis of a ruptured small aneurysm is difficult to predict accurately. According to few previous reports, entire recanalization was detected in DSA on days 14-19 from the detection of spontaneous thrombosis2,6,10). The time interval between follow-up imaging studies also differed between previous reports, ranging from 4-11 days2,6,10). We repeated the angiogram every week to check for the changes over time. In previous literature, the fastest detection of the time point of entire recanalization was 14 days from the first discovery of disappearance10). Although it is difficult to draw a definite conclusion, it seems appropriate to conduct the first follow-up angiogram within 14 days after detection of spontaneous disappearance.

CONCLUSION

The exact timing of the recanalization following the spontaneous thrombosis of the ruptured aneurysm is difficult to predict. Repeated angiogram is crucial for the surveillance of recanalization.

Notes

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.